When Phylis Walker graduated from Luther Jackson High School in June 1965, she became one of the last students to walk across its stage before its closure. Just a few months after her graduation, Fairfax County Public Schools completed the long-awaited process of desegregation, marking an end to the era of separate education for Black students. Luther Jackson, the only high school for Black students in the county, closed its doors as students began integrating into previously all-white schools.

Phylis was born in March 1947 in Washington, D.C. The need to locate a hospital willing to admit Black patients meant that she entered the world miles away from her hometown of Fairfax County, a place that, during her early years, promised a future of educational inequity. Growing up in a segregated society defined by Jim Crow laws, she navigated a world where public spaces and facilities were racially divided.

Her educational journey began at Drew-Smith Elementary School in Gum Springs, a segregated institution that boasted an all-Black staff dedicated to teaching students from kindergarten through seventh grade. From eighth grade onwards, Phylis transitioned to Luther Jackson High School, a decision that came about as a direct result of community activism.

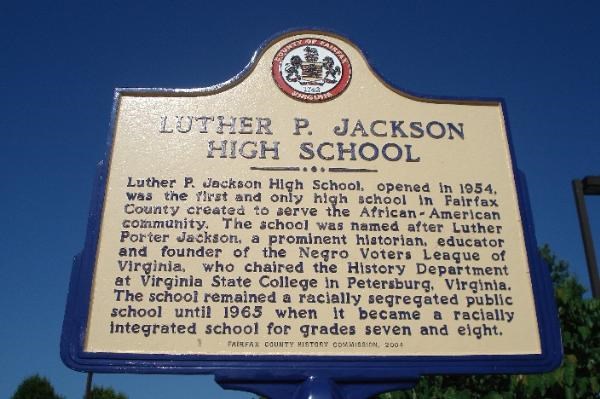

In 1948, just a year after Phylis’s birth, a group of eleven representatives from the local Black community approached the Fairfax County School Board, advocating for a “comprehensive Black high school.” Seven years later, Luther Jackson opened its doors, named after Dr. Luther Jackson, a notable historian and civil rights advocate recognized by the NAACP for his contributions to African American history.

Reflecting on her time at Luther Jackson over fifty years later, Phylis recalls the nurturing sense of community that enveloped the high school. In a 2021 oral interview, she shared memories of compassionate faculty members who were deeply invested in their students’ success. Despite the limitations imposed by segregation, she never felt disadvantaged compared to her white peers.

By her senior year, Phylis served as the associate editor of the “Jackson Tattler,” Luther Jackson’s annual newspaper, showcasing both her academic prowess and her contributions to school life. Her dedication culminated when she was recognized as Miss Homemaker of Luther Jackson, achieving high scores on the annual homemaking exam.

However, just months after her graduation, dramatic changes occurred. The closure of Luther Jackson High School followed the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which declared the segregation of public schools unconstitutional. Today, the former high school stands as Luther Jackson Middle School—a poignant reminder of the struggle for educational equity, now transformed into a beacon of multicultural education for future generations.

Phylis Walker-Ford still calls Fairfax County home and remains an ardent advocate for the preservation of Black history. In 2021, she served as a commissioner on a committee that initiated the Fairfax County African American History Inventory, a collaborative endeavor between the Fairfax County History Commission and the Center for Mason Legacies. This project aims to safeguard and celebrate the stories of Black history in Fairfax County, ensuring that the legacy of resilience and activism, which the high school and its alumni represent, continues to inspire future generations.

Transcript of her Oral Interview: Phyllis Walker-Ford

For more information on Fairfax County African American History Inventory visit: Fairfax County African American History Inventory | History Commission